This picture shows why you remove all canvas from the boat before the hurricane. The canvas on this boat's t-top was heavy-weight and well-stitched; the canvas suffered no damage. The T-top frame, however, is another story; because the canvas didn't rip, it caught the wind and acted like a sail, bending the frame.

This picture shows why you remove all canvas from the boat before the hurricane. The canvas on this boat's t-top was heavy-weight and well-stitched; the canvas suffered no damage. The T-top frame, however, is another story; because the canvas didn't rip, it caught the wind and acted like a sail, bending the frame.

If you keep a boat in the water through hurricane season in the tropics, you need to be prepared for the possibility of a hurricane warning in your area. Boats in the water will be subjected to high winds and waves and torrential rain, so they should be stripped of all sails, canvas, bimini tops, bimini frames, t-tops, and all unnecessary lines, and then sealed as tightly as possible. (You might want to lay in a supply of tarps before the storm hits, because they'll be in short supply afterward.)

The rule for tying up a boat for a hurricane is: there is no such thing as too many lines, nor too many attachment points on the boat.

That is so important that I'm going to say it again so you can't miss it:

During a hurricane, there is no such thing as too many lines, nor too many attachment points on the boat.

As the boat is pitched violently about, lines can chafe, cleats can pull out, pilings can break or pull out, whole docks can collapse, trees can fall down, and ground anchors can be bent or pulled up. Those are things I saw over and over after Hurricane Charley in Punta Gorda and Hurricane Andrew in Miami. Use every cleat on your boat for as many lines as it can hold, and run them to as many independent points on land as you can find.

Even in small canals and waterways, the waves get surprisingly large during a hurricane, and the boat will be flung against the mooring lines with great force.

I filled both amas of my trimaran with water and tied down the sailboat and trailer with every line I owned. After Hurricane Charley passed by, all the lines were slack. The trailer itself had actually moved several inches sideways.

I filled both amas of my trimaran with water and tied down the sailboat and trailer with every line I owned. After Hurricane Charley passed by, all the lines were slack. The trailer itself had actually moved several inches sideways.When you tie to a dock cleat, try to imagine suspending your entire boat from that cleat. Do you think it will pull out? If so, don't use it. Use a piling. If the pilings look weak, look for phone poles or trees. All types of palm trees are particularly hurricane resistant, as are water trees such as mangroves and cypress. If you have a choice, try to avoid oaks — because they're a very hard wood, they don't bend with the hurricane winds — they break instead, or are uprooted completely out of the ground. I tied my boat to an oak tree, and the oak tree fell on the boat.

Consider Ground Anchors

If nothing strong is available on land, consider using ground anchors. These are metal rods with a hook on one end and a single-turn screw blade on the other end. You screw them into the ground, and then tie a line to the hook. I used two of these, about two feet long and with a shaft diameter about the size of my finger. They bent and pulled up out of the ground. Now I have some six foot ground anchors with a much larger shaft.

Make A Ground Mooring, If Possible

If you know where you will tie your boat during a hurricane, consider installing a ground mooring by digging a large hole and putting a good sized piece of rebar bent into a U in the hole, then filling with concrete.

On your boat, use all your cleats to their maximum capacity, but also use any available lifting eyes and bow eyes. Hawse pipes, samson posts, winches, davits, seat posts, or anything else which is structurally tied in to the hull or deck of the boat should be used to tie lines to different shore points.

Anchors During A Hurricane

If you must put out anchors, put out large anchors, with plenty of chain and rode. To increase the effectiveness of your chain in extremely high winds, you can attach a mushroom anchor or other weight at the point where chain meets rope.

Chafe and the potential for failure at the attachment points are not the only reason to put out as many shore lines and anchors as you can possibly muster. One of the great dangers to your boat during a hurricane will be nearby boats that get loose. Your web of lines may help to stop loose boats before they slam your boat.

Consider Likely Wind Direction

Sometimes it is possible to predict the direction from which the strongest winds will come. Look around at any nearby boats, especially those you believe will be upwind. Do they have coolers, unsecured hatch covers, or anything else that might come flying your way? Do they have lots of lines to different points on land? Are the upwind lines doubled or tripled? If the answers are no, you may want to correct that situation if you have time. It doesn't take long to find a way to secure a cooler, but finding someone to fix your boat after a hurricane flings the cooler through it will be difficult and expensive. Boat repair businesses are pretty busy with this kind of thing after a hurricane.

If you take great care to tie up your boat, only to have a nearby boat get loose and smash through the side, your boat will be sunk and hanging from her mooring lines. A couple of lines on the other boat may have prevented that, and if the boat owner upwind of you is negligent or ignorant, you will pay the price. Don't just shake your head and wish that owner behaved differently when a hurricane is approaching. Take action. Remind yourself that you're not doing it for him; you're doing it for yourself.

Consider Storm Surge

Storm surge should be considered when tying up a boat for a hurricane. The water can rise 15 feet or more above normal high tide levels. For that reason, all lines should be as long as possible, led to the most distant points on land that are feasible. The rules for the use of spring lines and bow and stern lines apply to storm surge tides as well, but the distances must be larger because the tide may rise much higher than normal.

Hurricane Charley was predicted to bring 12 to 16 feet of storm surge to Punta Gorda, FL, but the actual surge tide was far lower. Why? Because of our protected location and the dynamics of storm surge.

Many people think storm surge is caused by the wind blowing the ocean up onto the shore on one side of the eye. The wind does do that to an extent, but the really high tides are not blown up by the winds; they are allowed up by the low pressure above. A storm surge tide is generated underneath the hurricane because a hurricane is an area of extremely low atmospheric pressure. Think of the atmosphere as a small layer of padding around the earth, and the low pressure of the hurricane as a spot which is worn thin, with less padding. That padding has weight. We don't think of air as having weight, but it does. It pushes down on the surface of the ocean, and if there is less of it in one area, that area of the ocean can rise up, forming a bump on the surface of the ocean beneath the area of thin atmosphere.

Other factors also affect the storm surge as a hurricane approaches land. A stationary hurricane will have a more or less symmetrical bump on the surface of the ocean underneath the center of low pressure, but a hurricane in motion has different dynamics. A fast moving hurricane will generate a kind of a ridge along its own path, as water is first drawn in under the approaching low, then squeezed back out as the hurricane passes by and departs.

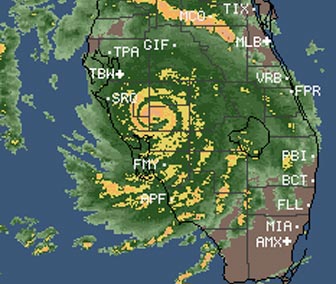

In this satellite image, the eye of Hurricane Charley is passing just a few miles from my home in Punta Gorda.

In this satellite image, the eye of Hurricane Charley is passing just a few miles from my home in Punta Gorda.A hurricane that is small in diameter but has a very low pressure at the center and very strong winds will generate a small, steep bump on the ocean, or will pull up a small but steep ridge if it is moving quickly. Hurricane Andrew was an example of such a hurricane. Very intense, but also small and moving quickly, it had storm surge tides of 16 feet just a few miles from my house, which was hit by the north eye wall. A storm with the same central pressure and the same maximum winds, but a larger diameter and a slower forward motion, could easily have dragged Biscayne Bay all the way up into my old neighborhood.

Hurricane Charley and Storm Surge

In the case of Hurricane Charley, Punta Gorda was also spared by the relatively small diameter and fast forward motion of that storm. We are also protected here by Charlotte Harbor and the barrier islands. Charley came right over a barrier island, cutting it in half, and that kind of thing will really slow down the ridge of storm surge that gathers under the storm as it passes. It's a speed bump. The relatively shallow harbor also creates some friction as the storm lowers the pressure over the harbor and draws in the Gulf of Mexico.

If a similar storm were to strike Fort Lauderdale, where deep water extends almost up to the shore, the storm surge would be far worse than we experienced here during Charley. By the time the low pressure of the storm could draw a whole bunch of water across the barrier islands and up into the Harbor, the storm had already marched across the harbor and was mostly over land, leaving higher pressure to fill back in behind and stop any further storm surge from gathering.

Storm Surge, Barrier Island Effects and Long Lines

We were protected by the barrier islands and the harbor, but oddly enough, that caused some damage to boats whose owners were trying to do the right thing. A huge storm surge was predicted, so they allowed enough slack in the various mooring lines to allow the boat to rise 12 feet or more and then get tossed around by large waves. When the the storm surge was far less than anticipated, the lines were not tight enough because the boats didn't rise as much as expected. The boats beat themselves up on pilings and docks.

Remember that lines stretch a lot under load. If you put out a line to a point 60 feet away and pull it almost tight, the natural stretch of the line will probably account for the slight increase in length needed at the highest point of the surge tide. As explained elsewhere, you should secure lines to pilings so as to be level with the boat when it rises to half of the predicted surge tide. Lines will chafe quickly in the violent pitching and rolling caused by a hurricane, so use chain at attachment and wear points where possible, then properly protect lines from chain shackles with chafing gear. Expired fire hose, leather, and old canvas or towels are popular choices to reduce line chafe.

The last two steps to hurricane preparedness for your boat actually take place on land:

- Get your insurance policies and anything else money can't replace.

- Leave. Do NOT stay on a boat during a hurricane. Do not stay in the path of a hurricane at all. I have already done that for you, and can report back that it is not something you want to experience.

I'll leave you with this last thought:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.